Earth, fire, water. Elements that have so much power and a life of their own; all touched and influenced by air.

I want them all in my life. More and more.

Just like surfing helped me understand life better. Appreciating the quiet, the moments of reflection and active wait, looking into the vastness of the ocean getting reading for the next wave. Fire seems to work in the same way or at least, that’s how I see it after the experience of this past weekend.

To do a successful wood firing one must listen to the flame, its sizzling sounds. A happy fire being one that is singing, well fed. Gone too quiet and it means it is slowing down. Time to tend to it, stock it. Wood logs going in in a specific way to make sure all the wood is being burnt. For being in the fire doesn’t necessarily mean that the wood actually is on fire.

What’s underneath? Is the ember bed working well — all across, evenly, able to quickly alight the new logs that on it are laid? Or is it all dead, unburnt wood underneath? Black and lifeless instead of the glowing bright orange burning embers needed to keep the fire going for eight (plus) hours without consuming an unnecessary amount of wood?

Just like us, like our bodies.

Are we stocking ourselves properly to keep going?

Or are we burning, going, working, moving, only superficially successfully? Give it a good stir. And see. Let’s look at what’s underneath and we’ll know for how much longer we might be able to keep going. We might be choking ourselves. We might come to a stall soon. And we just don’t know it. The surface misleading us. The façade a mere trompe-l'œil. A trick to the eye.

My friends Karina, Sayaka and I joined 10 strangers in Wytham Woods at Oxford Kilns to fire the fast kilns. Inspired by the Japanese anagama kilns, these smaller and faster kilns have been designed to foster community and teach people how to operate kilns, understanding the fire and its principles. A very accessible way to get closer to a tradition that can be very hierarchical, exclusive and daunting.

It only takes around eight to ten (if all goes well) hours to fire these kilns, opposed to the three to four days that an anagama kiln can take to do its thing. The speed also means that things can go wrong very quickly. Just like a wave that is poorly read and we get on it and the sea takes us deep in, unwanted.

We were lucky enough to meet Svend Bayer who gave a little talk to those of us present before opening his kiln on Sunday morning. Now in his 80s, Svend is the last man standing from a tradition of potters following the steps and teachings of Bernard Leach and Michael Cardew. A lifetime dedicated to pottery, wood kilns and fire that he kindly shared with us, showing us photos of the numerous kilns he has built and some of the pots he has made. As the time for questions arrived, I was curious to know how a life dedicated to the elements might have influenced his take on life and his own sense of self. He shared his thoughts mentioning it all is an obsession for which he has not found a substitute yet. The word ‘obsession’ pushed the conversation further, instead of moving onto the next question, and Robin, the man behind Oxford Kilns, asked is obsession necessary? A question I have not stopped thinking about since.

What am I obsessed with? Am I obsessed with any of my jobs? With clay? With art? With pots?

Off the back of Robin’s question, though I cannot exactly remember the thread of it all, a Scottish woman sitting next to me said that she was indeed obsessed, to which Svend asked — But how much? Obsessed enough to quit your 9 to 5 job? It seems she is for, she said, she is working on it.

So, am I? Are you? I don’t think I am. I am definitely a tad obsessed with sports, with triathlon at the moment, that is for sure. I think I am obsessed with learning about and experiencing how pottery has been doing and is still doing in certain parts of the world. I could give my all to that.

Making… I love it. But am I obsessed? Obsessed enough to just do that? Now fire… I could be obsessed with fire. I might be on the way.

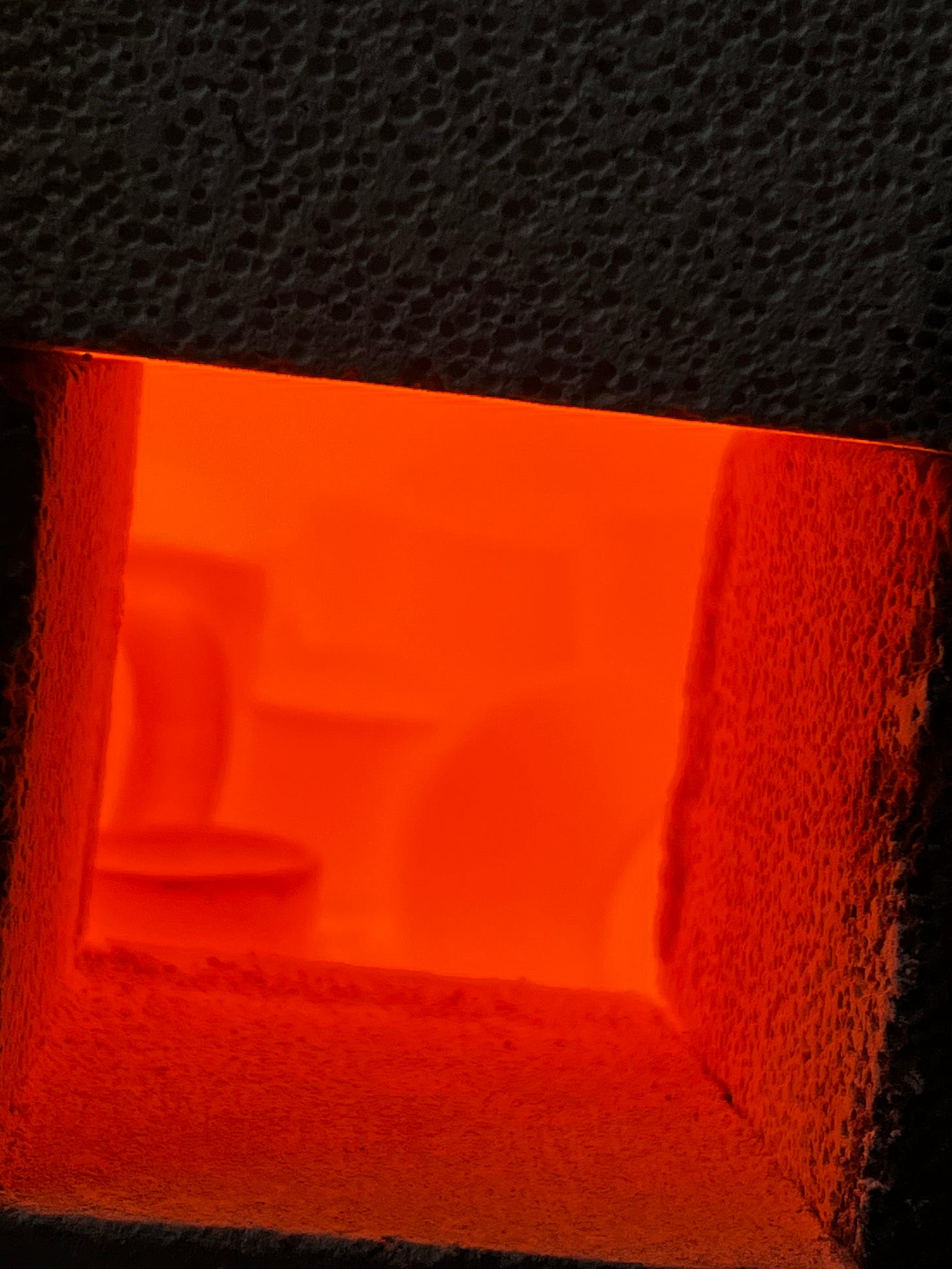

At some point when the kiln had reached about 1200C if I remember well, Ekta — our teacher, guide — said ‘now let’s ride the flame’. Meaning let’s follow its lead, let’s do what it tells us to do. Let’s be one with it. Too much dark smoke coming out of the chimney and we have too much wood unburnt underneath the embers. Not enough oxygen, the kiln going onto reduction (a firing process whereby the lack of oxygen in the atmosphere makes the flame take the oxygen from the surface of the pots and the glazes changing their chemical composition and consequently, creating different colours and effects). A bright orange flame and the fire is going well.

At that temperature, everything around the fire is impacted by it. Bricks that move, expanding the size of the kiln, the traces of the flame visible, coming out of the kiln into the open air. The heat travelling through my jeans, the denim too thin to block it, my legs burning. The frame of the protective glasses to be able to look onto the fire burning my forehead if too close to the fire to stock it. Gloves that no longer serve their purpose, burnt as well, fingers in absolute pain. Nothing is indifferent to a 1300C fire.

And neither was my soul.

We will probably be back in September to keep feeding that fire and this growing obsession. While I am definitely still high from the experience, camping and being in nature, I also can feel so much being processed inside me. Thoughts I am not aware of yet. New feelings and ideas slowing being alight. We’ll see where the flame takes me.

Crafts(wo)manship & Japan

From Svend Bayer’s views on crafts to Bernard Leach’s films from the potteries in Japan; some archival videos to accompany today’s piece.